An American’s observations of a first time trip to France.

*Normandy Landings

Omaha Beach – Pointe du Hoc – Sainte-Mère-Église – Normandy American Cemetery

A dog romps around this mostly quiet beach. There’s nothing quite like the unbounded joy of a dog on a beach, kicking up golden sand, and stopping occasionally to inspect the few people on this stretch of shoreline. Anyone walking this beach today is braving fouls weather; rain showers, high winds and blowing sand.

Bravery; it’s a relative thing.

Bravery occurred here eighty-one years ago, when over 1400 equipment laden men of the first wave of the Normandy invasion landed meters from where I’m standing. They were dropped far out in chest deep water and by day’s end the golden sand was stained red and strewn with equipment, the dead and the wounded (the Americans would suffer over 4000 casualties here).

Jesse Beazley, a rifleman with the Second Infantry Division was part of the invasion force that landed on Omaha Beach on June 6th, 1944. When his landing craft was blown up far from shore he was thrown into the water. Weighed down with equipment, he had the wherewithal to shed all his equipment in order to keep from drowning. Many of his comrades were not so lucky. With only his gas mask and his rifle, Jesse swam to shore as German bullets hit the surrounding water. Jesse Beazley survived the ordeal on Omaha and took part in the subsequent major campaigns of World War II.

Omaha is not unlike Utah Beach, which we’d visited yesterday. But for some monuments and plaques that tell the story of June 6th, 1944, this could be any beach in Northern California where I call home. There are of course the ghosts of those who didn’t survive to see the end of that day.

Of those who did survive, and who had the good fortune to survive the rest of the war, very few remain. Most, if not all of the still living, would be 100 years old. (In June of 2024, I was on a plane bound for St. Louis. A frail old man was sitting in first class. I’d first noticed him when he boarded. Needing assistance, he was one of the first to board the aircraft. Once the plane was well on its way, the captain announced that we had a veteran of D-Day on board. The crowd erupted in cheers. A short while later, the captain emerged from the cockpit to meet and shake hands with the old soldier).

The stories will live forever. Though the later generations have been slowly, and unfortunately, forgetting the events of that day, the truth of what happened here will always live. This beach will not forget. In this part of France the memories and the gratitude seem immortal. While the world is content to forget, “la Normandie” will always memorialize the Debarquement.

Just as it was yesterday at Utah Beach, I can only stand and try in vain to imagine the horrors of that day.

“Where tourists and vacationers see pleasant waves, I see the faces of drowning men,” writes Arnold Raymond “Ray” Lambert, in his book, Every Man a Hero: A Memoir of D-Day, the First Wave at Omaha Beach and a World at War. Lambert served as a medic in the 16th Infantry Regiment of the army’s First Division and was part of the first wave to hit Omaha.

“The noise of war does more than deafen you,” he writes. “It’s worse than shock, more physical than something thumping against your chest. It pounds your bones, rumbling through your organs, counter-beating your heart. Your skull vibrates. You feel the noise as if it’s inside you, a demonic parasite pushing at every inch of skin to get out.”

Wounded twice, Lambert saved the lives of more than a dozen of his comrades. Having administered a morphine shot to himself to mask the pain of his own wounds, Lambert rescued men from drowning, bound wounds, and helped to get other wounded to the shelter of a steel barrier. Lambert’s day ended when a landing craft ramp slammed down on him, breaking his back, as he was trying to rescue a soldier drowning in the surf.

Situated near the center of Omaha Beach is an imposing stainless-steel sculpture designed by Anilore Banon. It consists of a set of three wings and towers. A nearby plaque describes, in Anilore’s words, the meaning behind her work.

I created this sculpture to honour the courage of these men:

Sons, husbands and fathers, who endangered and often sacrificed their lives in the hope of freeing the French people.

Les Braves consists of three elements:

The wings of Hope

So that the spirit which carried these men on June 6th, 1944 continues to inspire us, reminding us that together it is always possible to changing the future.

Rise, Freedom!

So that the example of those who rose against barbarity, helps us remain standing strong against all forms of inhumanity.

The Wings of Fraternity

So that this surge of brotherhood always reminds us of our responsibility towards others as well as ourselves.

On June 6th, 1944 these man were more than soldiers, they were our brothers.

Below: If there’s any saving grace to the stormy weather, it’s the dark clouds looming over the English Channel, that make for some dramatic photos.

Pointe du Hoc

A fifteen-minute drive on a narrow farm road, takes us from Omaha Beach to Pointe du Hoc, a headland that juts from the French coast into the Channel. It’s main feature is a 110-foot cliff that rises from the crashing sea to the top.

Pointe du Hoc’s fame comes from the action of June 6, 1944 when the men of the 2nd Ranger Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. James Earl Rudder, were tasked with landing on the narrow beach and then scaling the cliffs using ladders, ropes, and sheer determination. Their mission was to destroy a battery of long-range German guns that sat atop the cliffs; guns that were capable of targeting the invasion force landing on Utah and Omaha Beaches.

We follow a winding path that passes the remnants of some German fortifications. Along the path is a series of markers that tell some of the personal stories of what occurred here that day.

All are inspiring.

Lieutenant James Eikner recalled a signature moment of his experience at Pointe du Hoc; “I was the last man off of my boat. Bullets were zipping by but none hit me, thank God. I got a hold of the rope right in front of me and started up and I got about two thirds of the way up and this hellish explosion. The last thing I saw was all of this mud, dirt, and rock coming down the cliff and I was knocked out. The next thing that I recall was I was buried up to about my waist. And I looked up and I could see this German up there looking down like that and he could have shot me right there if he wanted to but I guess he figured I was gone, you know. So I looked around for my rifle, I had a Tommy gun, and it was some feet away and I managed to squirm around and finally pull it out, and this fellow was still up there and looking round the other way and I took a shot at him, and pulled the trigger and it snapped, my gun was clogged up with mud. And there I was and I remember saying to myself, “Aint this a hell of a note, here I am in the damnedest war in history and I don’t have a gun.”

Others are heartbreaking.

June 6, 1944 was Sergeant Walter Geldon’s third wedding anniversary. Before landing at Pointe du Hoc, Walter’s comrades in Company C of the Second Ranger Battalion helped him celebrate the occasion in song. Before the war, Walter was a steelworker in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania – a regular working stiff. On June 6th, his task was to scale a vertical cliff in the face of German gunfire in order to take the summit and then knock out guns that were threatening the amphibious assault. Within minutes of coming ashore, Walter was killed by enemy gunfire. His widow, Walter’s wife of a brief three years, passed away in 2002 at the age of 78. Her last request was to be buried by her husband’s side.

The land is pitted with shell holes from the pre-invasion bombardment by the armada. One of the Rangers later described the scene at the top, “The bombs and naval bombardment had left the top of the cliff in such a state that it looked like craters on the moon.”

Once again we’re stymied by the weather as the path that approaches the cliff’s edge is closed, likely due to the winds and rain. With the trail closed, we’re not able to get a good view of the monument to the Rangers who scaled the cliffs. I feel bad for Cora’s cousin, Ayen, who, having watched a documentary of this part of the battle, was looking forward to getting a closer look at the cliffs.

Sainte-Mère-Église

After Pointe du Hoc, we’ve taken the drive to Sainte-Mere- Église on the southeast corner of the Cotentin Peninsula. The little town is all Airborne, all the time. Gift shops, museums, restaurants and lodgings bear names that recall the actions of the Airborne on June 6th, 1944.

It was the first hour of June 6, 1944 when Sergeant John Steele of the 82nd Airborne was gliding down towards the center of Sainte-Mère-Église. He was supposed to be landing near the town, and not in the main square. As Steele descended he was fighting to guide his path away from a burning building.

Below him, German soldiers were shooting at Steele and his helpless comrades. Already wounded in the foot from an exploding flak round, Steele’s chute got entangled on the on one of the spires of the 12th century church. After dangling for two hours, Steele was taken prisoner by the Germans. Four hours later, Steele escaped and rejoined his comrades.

(John Steele’s experience was made famous in the movie, The Longest Day, in which Steele was played by actor Red Buttons).

In a little village that could be famous for its charm, the main attraction is a mannequin of John Steele, dangling from a parachute tangled on the church tower (just a two minute walk from the church is the hotel – restaurant, Auberge John Steele).

Below: “John Steele” dangles from Notre-Dame-de-l’Assomption church

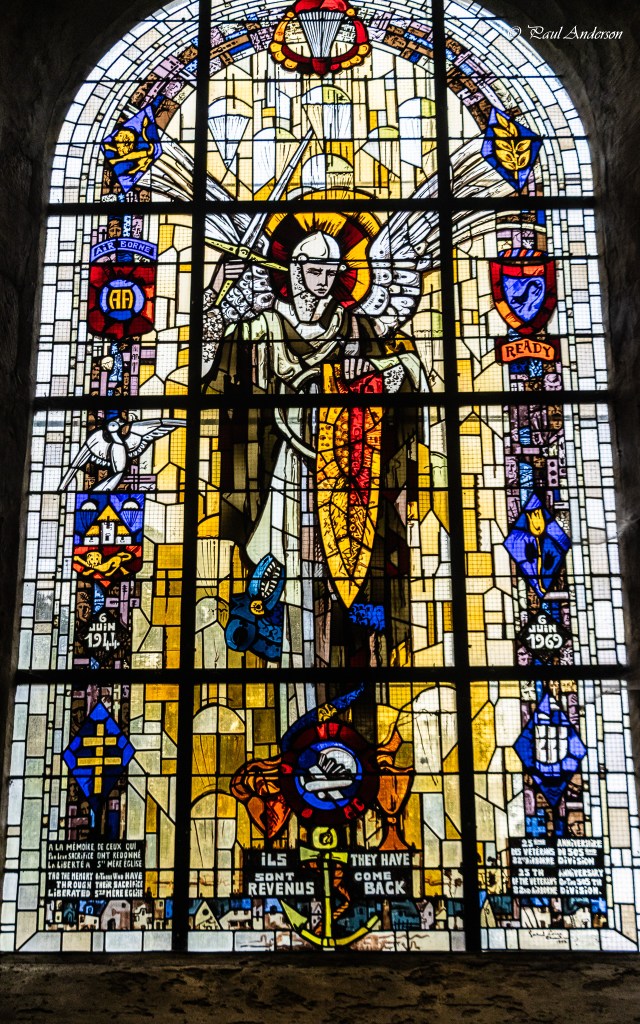

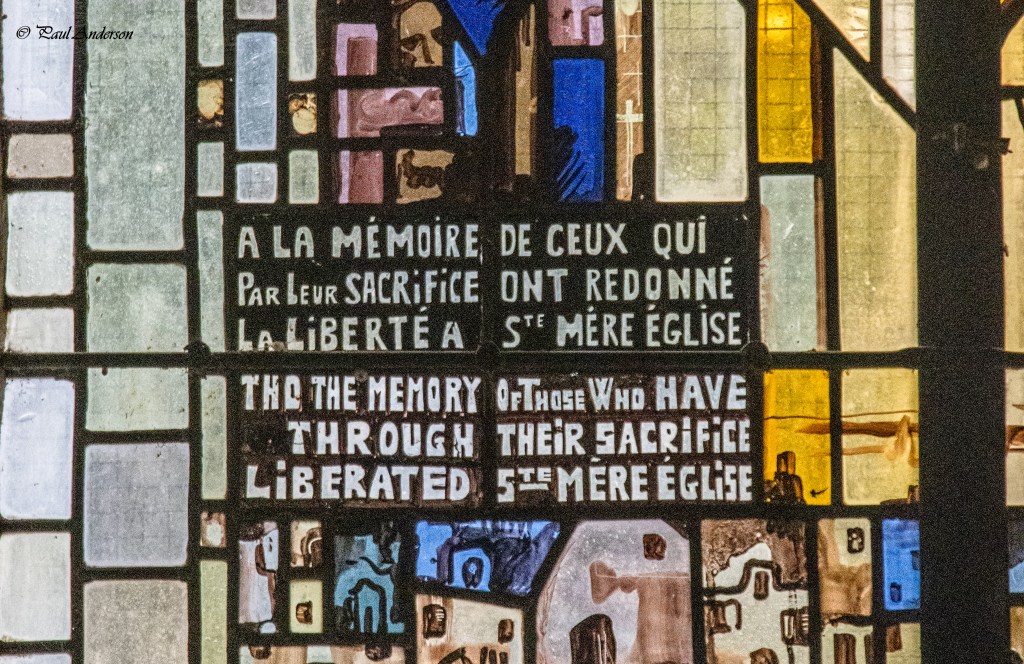

The church here is like many of the old churches that we’ve visited in the French villages but with one distinctive difference that I notice just as we’re about to leave. I take a close look at one of the stained glass windows; it’s a tribute to the Airborne. Another window nearby is likewise a tribute to the Airborne.

Looking at the window I’m both touched and ashamed. The people of this region have not forgotten what America, Great Britain and Canada did on that June day and in the days following.

And yet in the decades since, Americans have, for no apparent reason beyond ignorance, decided that it’s fun to malign France. Most recently the slander has come from three disreputables in high office; the Vice-President, the Secretary of State, and the Secretary of Defense who clearly have no appreciation for the partnership that dates all the way back to the American Revolution. Certainly, they know the history, but out of their own belligerence they’ve chosen to marginalize the past. The President? It’s doubtful that the self-absorbed narcissist has a clue about the history, much less the partnership.

Our visit is limited to a walk through the church, a quick stroll through town and a bathroom break. Before leaving we hit a patisserie,

because

it’s France.

I’d like to stop and visit the Airborne Museum, but Sergeant Cora must have read my mind. Before I can even make the suggestion she issues the order, “no more museums.”

Normandy American Cemetery

I’ve purposely planned the day so that our last visit is to the American Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer. That this stop is on the way home is one reason, but the main reason is that it will likely be the most somber part of the visit. Out of respect it isn’t something to be rushed.

The cemetery is located on the high ground that overlooks Omaha Beach.

The visit starts at a Visitors’ Center where there’s a short video. After the video we walk through a display area where the stories of some of the fallen are chronicled. This is not like most museums, where voices echo around stone halls. It’s quiet here. Voices remain hushed.

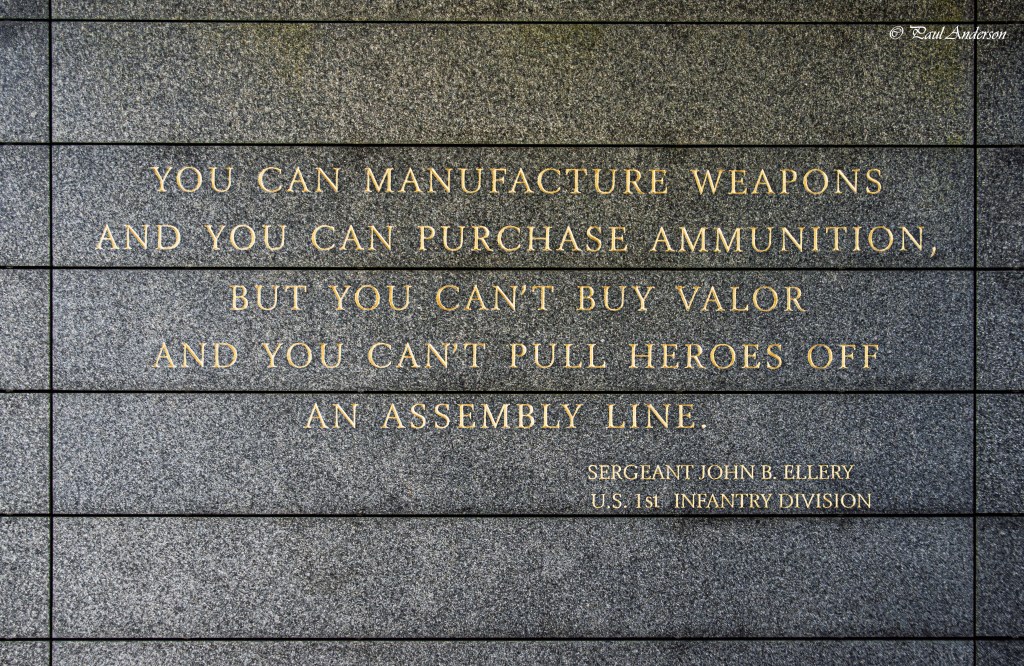

Just outside of the Visitors’ Center is a pool that looks out onto Omaha Beach. A left turn takes you into the cemetery itself; 172 quiet, emerald acres. This is the final resting place for over 9400 who perished in the liberation of Europe. It’s the final resting place for three Medal of Honor recipients, and forty-five sets of brothers. Most of the markers bear the names of the fallen. Some bear the inscription, “Here Rests in Honored Glory a Comrade in Arms Known But to God.”

The weather has improved slightly. While the wind is incessant, the sky alternates between partly cloudy and brief light showers.

The wind and the occasional rain shower fails to detract from the serene beauty of these grounds; the meticulously manicured lawns, shrubs and trees; the monuments; a reflecting pool, and a chapel. Looking west from the cemetery, billowing white clouds against a sky so blue it almost hurts the eyes, drift over the wind tossed English Channel. Standing in this serenity you couldn’t imagine the horrors of D-Day

but the evidence is right at your feet in a sea of white markers.

Suckers and losers

Walking amidst the markers I’m dogged by anger.

“Suckers” and “losers,” he said. Standing in this paean to sacrifice I can’t push away the rage I feel over Donald Trump’s characterization of the fallen as, “suckers,” and “losers.”

In 2018, President Donald Trump begged off of a visit to the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery near Paris; a cemetery where the fallen of World War I rest. He blamed foul weather, but that claim turned out to be untrue. In conversation with an aide, Trump remarked, “Why should I go to that cemetery? It’s filled with losers.” During the same trip he referred to the fallen soldiers as “suckers.”

Some doubt has been cast on that conversation, but in an interview with CNN, Trump’s former chief of staff John Kelly, a retired Marine general, corroborated the story.

In an earlier incident, on Memorial Day, 2017, Trump visited Arlington Cemetery with Kelly. The two men paused in front of the grave of Robert Kelly, the general’s son. Robert, a first lieutenant, had been killed in action in Afghanistan. Trump turned to Kelly and said, “I don’t get it. What was in it for them?”

Believing these stories isn’t a hard thing. Since his first campaign, Trump had established a history of maligning soldiers. In 2015, Trump said of John McCain, a former combat pilot who was shot down and imprisoned in North Vietnam, “He’s not a war hero. I like people who weren’t captured.” When flags were flown at half-staff, following McCain’s death, Trump angrily told aides, “What the fuck are we doing that for? Guy was a fucking loser,”

Jeffrey Goldberg. Trump: Americans Who Died in War Are ‘Losers’ and ‘Suckers’. The Atlantic. September 3, 2020.

There is a long line of American warrior presidents, beginning with George Washington, and on up to George H.W. Bush (who was also maligned by Trump as being a “loser” for being shot down by the Japanese during World War II). America is now saddled with a president, the Commander in Chief of the armed forces, who famously dodged the draft.

As I pass by the markers and read the names of young men who gave all, it occurs to me that Donald Trump is in fact a jealous coward. He’s certainly a bully, and by their very nature bullies tend to be cowards at heart. I’ve no doubt that the men who rest here present a personal threat to Donald Trump because they showed the courage and selflessness that is beyond Trump’s understanding. They are admired for something that Trump knows he can never be lauded for.

Forgetting the past

Even before we’d arrived at Normandy, I began to realize how history is slipping away, becoming more unimportant as the generations pass.

Somewhere between Paris and Normandy we stopped to get something to eat at the French version of a travel center. As we snacked I noticed men sitting at tables and shopping in the souvenir stores. All of these men wore lanyards that read “Beaches of Normandy.” It was a tour group, headed for the same destination as us. The men all looked to be fifty years old, or older.

As we visit the monuments, museums and battle sites I can’t help but to notice that the middle aged and younger are a rarity.

In one sense it shouldn’t surprise me. I’m one generation removed from what has been termed the “Greatest Generation.” When I was a child, our next-door neighbor had served with the British Royal Navy. Next door to him lived a man who’d served under Patton. Across the street from that man lived, Doug, who’d been a bombardier in a B-29 in the Pacific Theater. My own father served in Europe. The “Greatest Generation” is down to a precious few and the generation following, my own, is beginning to dwindle as well.

It’s personally gratifying that my own son has an appreciation of history and especially of the events that occurred in Normandy. But he seems to be a rarity among his contemporaries. And it appears to get worse as the generations follow.

I feel the diminution of the importance of history. I felt it a year ago when we were in Poland and toured Auschwitz. It was an older group who walked through those horrific barracks. (A recent survey revealed that two-thirds of American millennials don’t know what Auschwitz is).

“Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

Whether it was Edmund Burke who said it (or some version of that famous quote), or George Santayana, or Winston Churchill, is of no matter. It’s the wisdom that’s of consequence. Wisdom that the world too often chooses to ignore.

The world, particularly Germany, ignored it in the 1920s.

My America is ignoring that wisdom as I write this.

That’s a wonderful photo of Banon’s sculpture, Paul. And your account of visiting these sites is both interesting and sobering.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Audrey. I hope that the meaning behind Banon’s work and words can strike a chord with all who visit.

Paul

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another powerful account of your visit to the Normandy beaches and some important reflections. Your photos of the Anilore Banon sculpture are appropriately dramatic and I was struck by a line in her description of the work, ‘together it is always possible to changing the future’. I hope that’s true.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Sarah. Thank you for the kind words.

Regarding your hope about changing the future. These are definitley troubling and bleak times in which it’s hard to see a bright future. Ms. Banon wrote that it’s “always possible.” It’s up to mankind to make the possibility a reality. How much bleaker if we don’t hold onto the belief that prospect can be turned into existence.

Thank you for reading and commenting.

Paul

LikeLiked by 1 person