My San Francisco is a series of posts that describes my own personal relationship with The City. My San Francisco pieces might be photo essays; they might be life stories, or they could be commentaries. My impressions aren’t always paeans to San Francisco; it’s a beautiful city, but like any beautiful city, it has its dark side and its ugly stories. These pieces will always have one common theme; they are expressions of my personal San Francisco experience.

“To some extent, the cult surrounding black-and-white photography is based on nostalgia” – René Burri

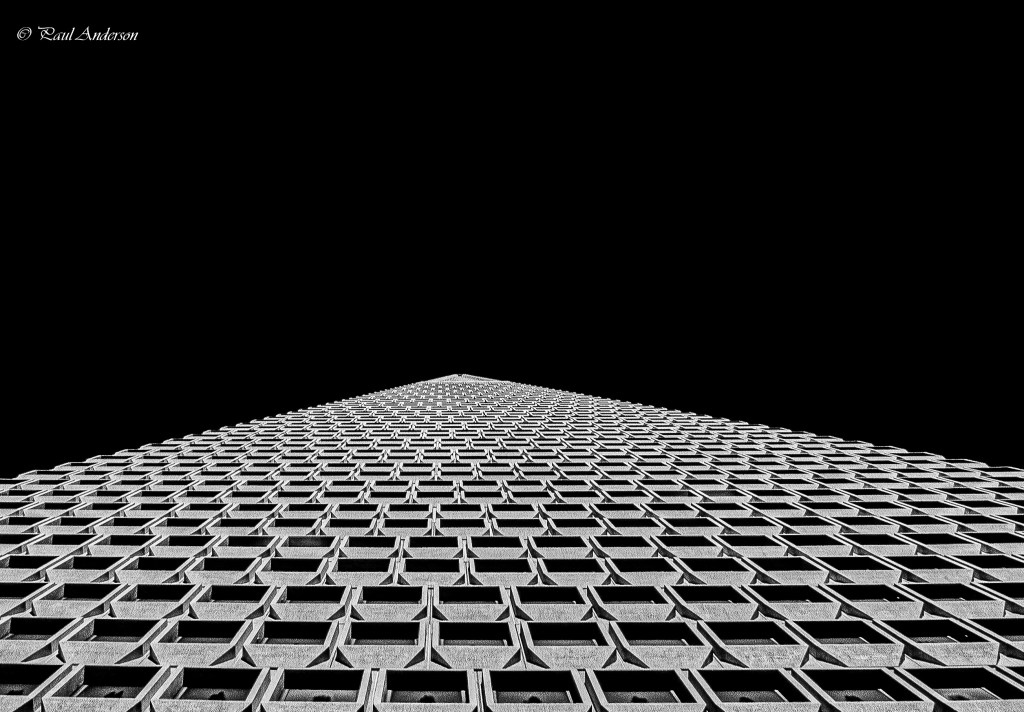

Maybe Monsieur Burri has a point. I originally shot the image below from Embarcadero Center, looking up Pine Street. In color. I sort of despised it and so it languished in the archives for ages until I started dabbling in monochrome. On a whim I edited the image into monochrome and the first thought that came to mind is that it reminded me of something that I might have seen in an ad in the San Francisco Chronicle, circa 1959. I don’t love it, but I do like the nostalgic newsy feel about it.

Maybe my attraction to noir fiction, the dark, brooding crime stories starring anti-hero, hard boiled gumshoe detectives, is also nostalgia based. And so I guess it’s only natural that I gravitate to shooting photos in alleys and darkening the mood of the images. The image below was taken in an alley near San Francisco’s Financial District.

The image below of Jaspar Street creates a far different mood in the color version, in which the buildings at the end are quite colorful in pink and green pastels.